- Share via

Gordon Leon dodged low-hanging trees as he crisscrossed his way up to yet another battle in his war against this unpredictable hillside.

The incline isn’t especially steep, but the path is uneven and narrow, at times even precarious. Still, the 72-year-old Leon easily handled the 10-minute climb to reach a makeshift dam he and a determined crew of neighbors had pieced together with bags of concrete below a small spring.

“Fifteen gallons per minute running out of what geologists call a ‘seep’ in the canyon,” he explained.

Anywhere else in California, such a natural water source might be celebrated. But here, near the most active portions of an accelerating and expanding complex of landslides known to be triggered by groundwater, it’s like dry brush next to an open flame.

The dam — just a few feet high and maybe 7 feet across — aims to direct water into a flexible black tube about as wide as a man’s thigh. The pipe snakes down the hill about the length of a city block to deposit the water into the local drainage system, thus preventing the liquid from seeping into the ground.

Leon leaned down to inspect how the concrete bags were holding up against the babbling water. No issues — yet.

There’s no guarantee the little dam will slow the escalating land movement that has caused untold damage across this corner of Rancho Palos Verdes. But Leon is hopeful it could help.

“We’ll see,” Leon said. “Everybody is on edge.”

Scores of residents are facing an impossible crossroads: abandon their homes and beloved community or devote umpteen hours and money to fight a landslide that geologists still don’t fully understand and can’t predict when, or if, it will slow — much less stop.

Leon doesn’t hesitate. He’s not leaving as long as he has any say in it, a sentiment echoed by many in this community.

“We will do what we need to do,” Leon said. “There are a lot of people actually fearful of it — fear is debilitating. It doesn’t solve anything.”

He chooses to get to work.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

◆◆◆

A retired aerospace engineer, Leon has essentially made a second career in landslide mitigation.

When he’s not building a dam from scratch, he spends his days filling new fissures, answering neighbors’ questions on his often-ringing cellphone and tending to the community’s network of “de-watering” wells, which pump out groundwater from the soil’s clay layers that become soft and slick when wet.

He struggles to describe how the land keeps moving, the damage keeps worsening.

“It’s surreal,” said Leon, who lives near some of the most dramatic movement, measured at around a foot a week in some spots. “You can’t predict where the different sections of the landslide are going to break apart.”

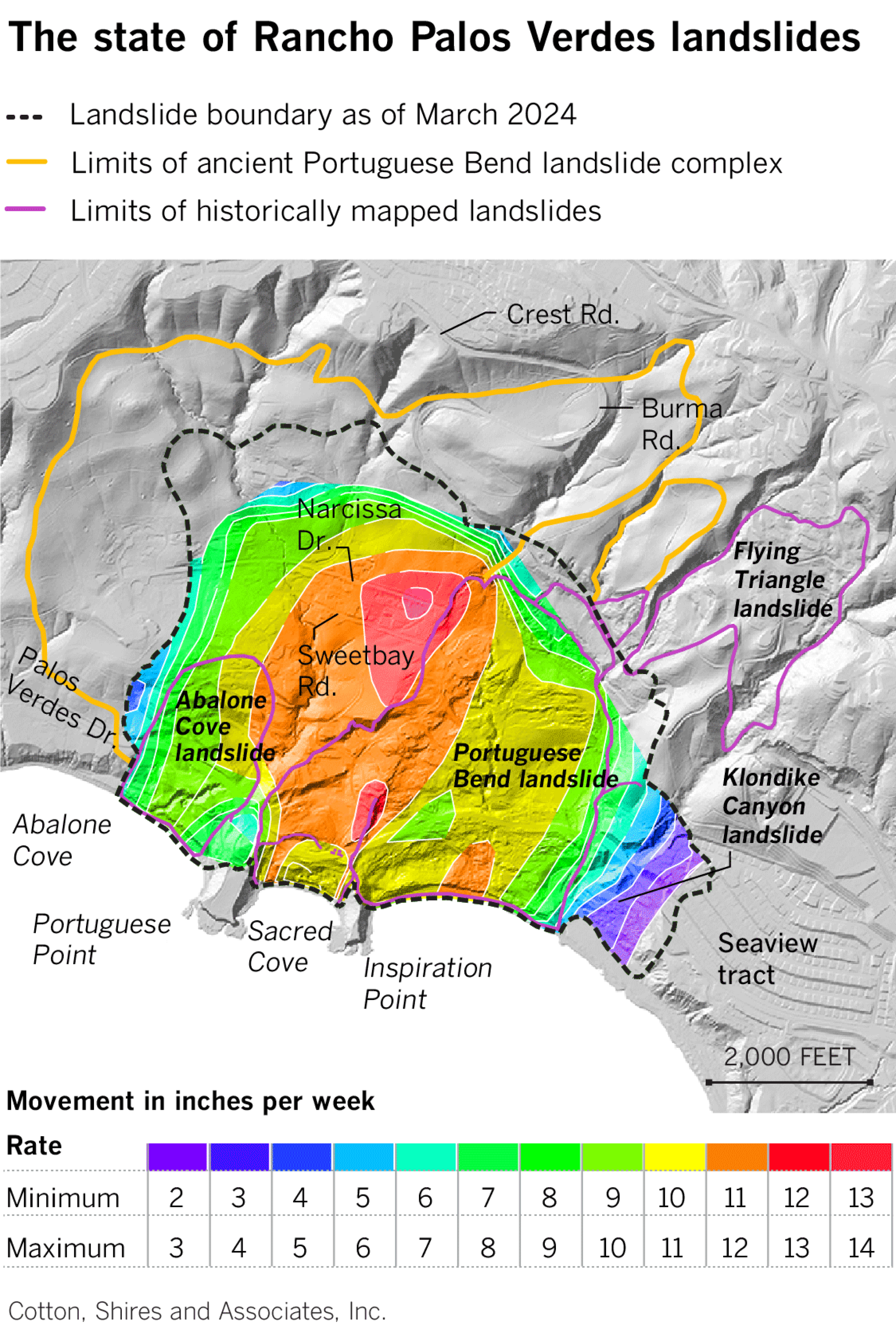

For decades, the fluctuating shifts that threatened the Abalone Cove, Portuguese Bend and Klondike Canyon areas of Rancho Palos Verdes — making up the majority of the ancient landslide complex still wreaking havoc today — were largely manageable with mitigation and monitoring. But back-to-back years of heavy rainfall after a severe drought have ignited a new kind of wrath from beneath the region’s oceanside cliffs and picturesque hillsides.

“It just seems to have set this thing off,” said Mike Phipps, the city’s geologist. It’s “just totally different behavior than how it acted for the last 40 to 60 years. ... This is a monster of a landslide we’re dealing with, and it’s moving at a very real clip.”

The recent movement of 2 to 13 inches a week — a pace that continues to accelerate over a footprint that keeps expanding — has fractured homes’ walls, forced open roofs, sheared countless underground pipes and transformed the landscape in several areas. It’s creating new coastline as land shifts seaward, and prompted the Southern California Gas Co. to cut off service indefinitely to 135 homes. There’s a real possibility that electricity could go next.

About 400 homes sit atop the landslide complex, an area covering about a square mile.

Some residents have left. But nearly all — like Leon and his family — remain, reworking drains in the middle of the night, spreading gravel over pavement that’s become unsalvageable and dipping into savings to do repair work that often lasts only a few weeks.

◆◆◆

Leon’s campaign against groundwater puts him and this corner of Los Angeles County at odds with the rest of the state, which remains hyperfocused on recharging aquifers to prepare for an all-but-certain future drought.

But here, drier seasons and parched earth would probably ease the dire situation.

“It would be great if all the wells were dry,” Leon said, as he snapped a picture of the meter on one of the neighborhood’s newest de-watering wells. (It was far from dry, pumping out about 20,000 gallons a day in its first few weeks online.)

The community’s fleet of 22 wells pumped, on average, a total of about 95,000 gallons a day into the ocean in the last year, according to the Abalone Cove Landslide Abatement District. The volunteer-run assessment district that Leon chairs monitors and works to control the smaller slide that borders the Portuguese Bend landslide. Six wells were installed here in the last few months; the rest have been pumping away for years.

But frequently, the wells break, shear or malfunction. On this June afternoon, 20 of the 22 in place were functioning. As of early August, the count was down to seven.

“The number’s different every week,” Leon said as his pickup truck rattled on the neighborhood’s bumpy roads with tools and replacement parts. “Is it an electrical problem, is it a plumbing problem, or do we need to replace the pump?”

He can share details about each well as if they’re his grandchildren: No. 8 is one of the originals that helped the community declare victory from this section of the landslide in the 1980s; No. 23 was recently drilled, but the pipe sheared before they could situate the pump at the bottom of the 100-foot well; No. 14 is one of the “more productive” ones, routinely sending 10,000 gallons a day, or more, into the Pacific. (Leon said local farmers have tested the groundwater for potential irrigation use, but found it too salty, requiring extensive treatment for it to be economical.)

“It’s like a PhD, in a very narrow area,” Leon said, laughing. “I had one geology course in college, and now I’m laser-focused on the geology on this landslide.”

Somehow, the home he and his wife share in upper Portuguese Bend has been largely spared from damage, but the house where his daughter’s growing family lives, less than a mile away, has sunk significantly.

“We’re making it work,” Leon said of a project aimed at stabilizing the foundation at his daughter’s home — as long as the movement doesn’t worsen. “I’m hoping it starts slowing down.”

But he knows there’s no guarantee.

“We’re almost doing [repairs] every couple weeks, and the cracks just form within 24 or 48 hours,” Rancho Palos Verdes City Manager Ara Mihranian said of Palos Verdes Drive South, a key artery for the region that has also seen worsening damage.

The city spent more than $2 million this year trying to maintain the one-mile stretch of affected roadway, three times the budget from 2022.

City leaders have also directed much of their energy into a $10-million emergency hydrauger project, a plan to drill two massive horizontal de-watering wells into the Portuguese Bend landslide, the largest and most central in the complex of five slides. That work began this summer.

Yet the emergency continues to intensify. With the threat of further utility cutoffs, the mayor this month sent a letter requesting state and federal assistance for further landslide repairs, as well as for individual residents.

Leon would love to see more aid to respond to the mounting disaster, but it’s been a slog to secure any significant funds.

He’s set up meetings with local politicians to advocate for increased assistance and is working with FEMA to try to offset costs from combating the land movement, ever since Los Angeles County was included in a federal disaster declaration for the string of atmospheric river storms in February.

Rancho Palos Verdes officials are also hoping to utilize that disaster declaration for reimbursement of landslide mitigation, but none of that money has been allocated.

Landslides are usually not covered by the California Disaster Assistance Act, which can provide financial support and local aid after a natural disaster. Earth movement is also generally not covered covered by typical homeowners insurance policies.

But a landslide is “every bit as devastating as something that happens like this,” Leon said with a snap of his fingers.

He recently showed state Sen. Ben Allen (D-Santa Monica) that reality when the lawmaker toured the area. Allen, who represents the Palos Verdes Peninsula, has proposed changing state law to explicitly include landslides among the causes for a state of emergency, something Leon said could open up a lot of needed financial support.

But the bill, SB 1461, has stalled in recent weeks. Many of his fellow legislators, Allen said, have been stuck on the notion that earth movement is a preexisting issue, not a spur-of-the-moment disaster.

“This is a preexisting condition in the way that living on an earthquake fault is a preexisting condition,” Allen said. “We don’t turn our backs on people once they’re living in these places.”

◆◆◆

The roots of today’s problems were planted in 1956, when construction reactivated part of the Portuguese Bend landslide complex — jump-starting the region’s ongoing seaward creep. The initial movement was devastating, slowly tearing up more than 100 homes and a beachfront clubhouse, but it remained relatively confined and eventually slowed with mitigation work.

Wayfarers Chapel, for example, wasn’t affected by the landslides’ initial movement and for 70 years remained relatively stable, with regular repairs and maintenance.

Now, though, the chapel has been dismantled and its parts put in storage.

“The earth is moving and there’s just nothing we can do,” said Dan Burchett, Wayfarers’ executive director.

In an effort to keep a continuing landslide from destroying Wayfarers Chapel, officials said the Rancho Palos Verdes structure would soon be disassembled.

Chapel leaders hope to eventually rebuild the historic landmark, but the deconstruction has bought them time to determine what will come next without the threat of losing everything.

Others aren’t so lucky.

On Exultant Drive in the Seaview neighborhood, about a mile southeast of where Leon lives, the road is getting harder and harder to navigate, and the foundation under Nikki Noushkam’s house is crumbling.

“We are in the process of abandoning our homes,” said Noushkam, who lives not far from two homes that were declared unsafe to enter in September due to landslide damage. “I have started moving some of my stuff out. … Quite frankly I am scared.”

But like so many others in the area, she never had a Plan B. She planned to retire in the home she bought in 2005, which she said had no prior landslide issues.

“Now I find myself in a situation, at this stage in my career, that I have to potentially start all over again,” the 49-year-old engineer said.

Like most of her neighbors, Noushkam would like to see the state and federal government provide direct assistance and guidance in the landslide fight, noting that the Abalone Cove and Klondike Canyon landslides are being managed by volunteer, civilian boards with small budgets.

“This is over everybody else’s head,” Noushkam said.

Leon’s driveway recently dropped several feet in just a few hours, and one of the two roadways providing access to his neighborhood became impassable.

After the utility issues, he’s started working on plans to convert his home to solar power — an off-grid, above-ground energy solution.

Yet, somehow, he’s staying positive.

“We’re really hoping that this next winter is La Ni?a” — associated with drier years in California — “and we have lower than average rainfall,” Leon said. “It’s a lot less efficient to take water out of the landslide than it is to put it in.”

On a recent Wednesday morning, he interrupted two construction workers who appeared to be filling cracks on a neighbor’s driveway with sand instead of using a sturdier substance, like clay.

“You need to fill the cracks with something impervious,” Leon said.

Later, he noted other repairs in the neighborhood, planned projects and needed fixes.

“It’s like Whac-A-Mole,” Leon said with a smile.

And he’s not giving up.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.